The Appropriation of “AMERICAN”

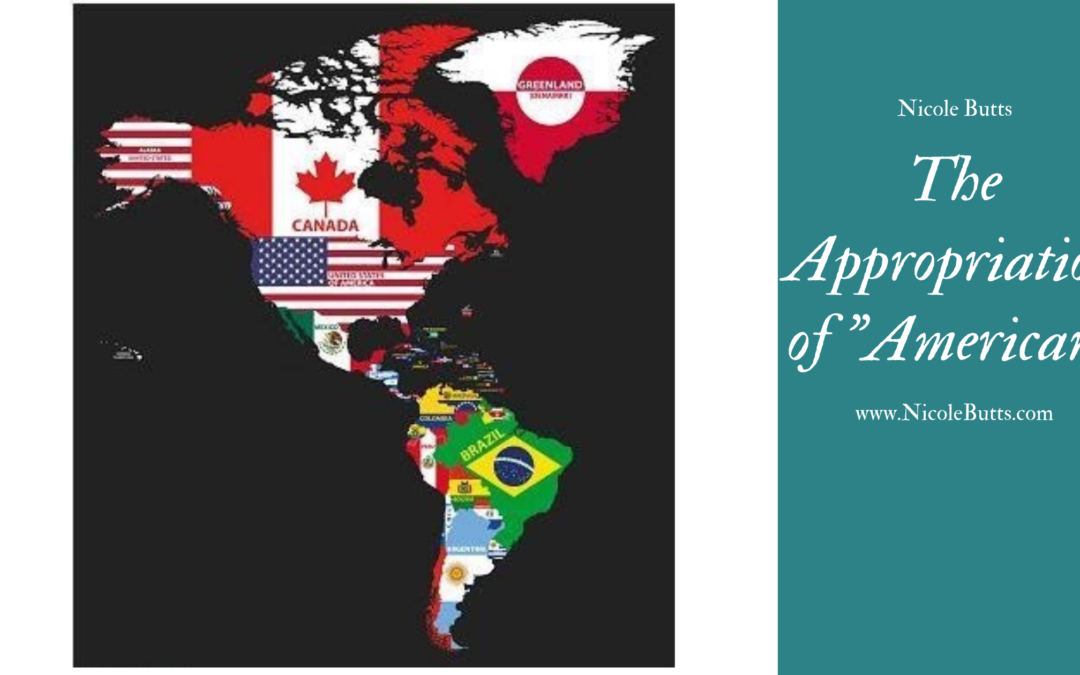

In what ways might your language be erasing “others”? For people living in the United States, it might be surprising to realize that America is a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. While the United States of America is part of America, America is not the United States. The United States is just one of the many countries of the Americas.

The five largest cities in America are Sao Paulo, Brazil; Mexico City, Mexico; Lima, Peru; New York, United States; and Bogota, Columbia, respectively. Multiple languages are spoken in America, including Spanish, English, Portuguese, and French, to name just a few.

Why am I pointing this out? Because language matters, as does erasure. Unfortunately, some in the U.S. have commandeered the term “American” as synonymous with whites in this country, subsequently erasing all the other countries and peoples of America. When Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell referred to voting Americans, he illustrated how he and others living in the United States have simply taken “American” as their own.

The appropriation of the term American to represent those in the United States—and more specifically, whites in the United States—is no different than if whites living in Great Britain referred to themselves as European, to the exclusion of all other nations and people on the continent.

Enter colonialism. Now I realize simply using the term “colonizer” is highly offensive to some and that those same individuals who feel offended would argue that colonialism is over, yet claiming the name of a continent as your own to the exclusion and erasure of all the other nations and people on the continent suggest otherwise.

I am a citizen of the United States. On my passport and all U.S. passports, it reads United States of America under Nationality. It does not read American. Being white in the United States does not make one an American and everyone else not American.

The words we use not only communicate what we are thinking, but also shape the very way we think. I challenge us to interrogate our use of language. In what ways does your language reflect your beliefs, assumptions, and bias? How might your language appropriate, erase, and otherize? How can you make your language more inclusive?